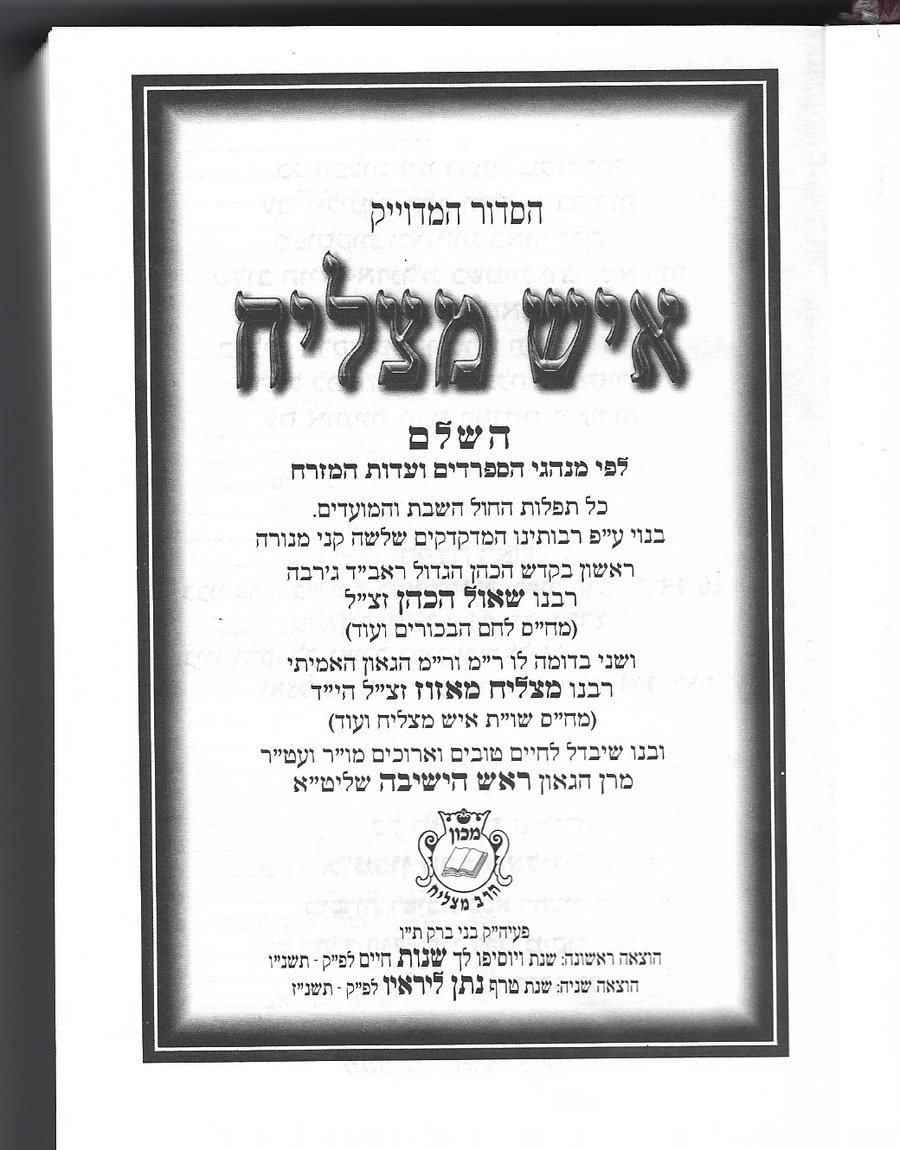

The introduction to the Ish Matzliach siddur, written by Kisei Rachamim rosh yeshivah Rabbi Meir Mazouz in 1996, explained the primary goal of the siddur itself:

“With the passage of 25 years (half a jubilee) since the death of our father, our teacher Maran Hagaon Rabbi Matzliach Mazouz, the heart of the administration of the yeshivah, may it be established in justice, was stirred for a good thing, to published a prayer siddur that is impeccably precise.”

And indeed, unlike many other siddurim, whose production was driven by economic, aesthetic, and sometimes even ideological-political motives, this siddur – as well as other books produced by the yeshivah – was created first and foremost by the desire to issue a siddur that was as exacting as possible, based primarily on the careful traditions and prayer formula of the Jews of Djerba and Tunisia.

These included Rabbi Shaul Hacohen and Rabbi Matzliach Mazouz, the father of the rosh yeshivah, who was murdered in Tunisia in 1971 by a Muslim assassin. This nusach includes quite a few changes – even if ostensibly marginal ones – compared to the more conventional Sefardic and North African nusachim.

For instance, one of the most significant and prominent changes included in the siddur – and which naturally attracted much attention – was changing the ancient appeal to God nakdishach [We will sanctify you] to another grammatical form nakdishcha, as well as a large number of additional changes, in almost every portion of the siddur.

To these we can add the “dikdukei abia”h” (“brief grammatical rules needed for the siddur”), as well as a booklet attached to later editions known as “Le-Ukmei Girsa [To establish the (proper) version]: Redactions and Comments in the Prayer Book,” which includes 120 detailed items regarding the various changes in the siddur, as well as their sources and roots.

When it came to design, the siddur’s editors chose to primarily use the common and popular Frank-Rühl font. However, due to the integration of collections of short halachahs throughout the prayers (as well as a consistent listing of the changing names of God, various points of focus or kavanahs, and even a brief commentary on some of the siddur), substantial parts of the siddur ended up being very visually busy, which may have deterred those who had no need for its “impeccable precision.”

The very thickness of the siddur – numbering almost 900 pages, albeit fairly thin ones – probably made things somewhat hard for regular users.

Still, despite these challenges, the siddur has managed to establish itself among significant numbers of communities and scholars in its almost thirty years of existence: not only Jews from Djerba and Tunisia, who are zealous in preserving their customs and ways of their fathers, but also others who enjoy the care, precision, and grammar and also the courage to decide in favor of one approach over the other rather than split the baby.

Nevertheless, things were not that simple: the great sensitivity accompanying the synagogue world as such – and the world of prayer and nusach in particular – led to the siddur receiving both very positive comments but also a great deal of piercing criticism from Rabbis and various figures. The criticism came from different angles: religious conservatism as such, the desire to cling to the familiar communal nusach at any cost, even if it itself was not entirely accurate, and specific arguments regarding some of these changes, which some scholars do not believe to be sufficiently well-established.

Thus, within a few years, the Ish Matzliach siddur earned the dubious distinction of being the target of a religious pamphlet attacking its existence, with the 2004 publication in Bnei Brak of the book “To Fence a Breach: On the Serious Changes and the Serious Breaches, New Things Which Our Fathers Did Not Conceive And the Great Obstacle of What They Called […] The Precise Siddur.”

On the other hand, ten years later, Rabbi Mordechai Mazouz responded with a detailed rebuttal and defense – entitled “A Mistake Always Repeats” – meant to “clarify the unique justice and truth of the Ish Matzliach siddur, and to reject dozens of comments they wrote on its nusachs […] which turn out to be but mistakes in reading and understanding of young students who falsify letters and articles under various Rabbis.”

In the end, despite the sometimes fierce disputes, the siddur became a fairly accepted part of the prayer libraries of many a synagogue throughout the country. This was likely also due to the unique status of Rabbi Meir Mazouz, the rosh yeshivah of Kisei Rachamim, whose greatness in Torah and independent status on many public issues helped to lead to the siddur’s distribution with his encouragement and inspiration.

Either way, the various writings for and against the siddur since it was first published are in itself a fascinating chapter in the history of Israeli prayer and siddurim, when clearly communal traditions were renewed and general, unifying nusachim were undermined.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.