Shortly after the appearance of the two nusachim of the Rinat Yisrael siddur – first Sfard (1970) and then Ashkenaz (1973) – it was clear to all that this project would have dramatic consequences, leading to a true revolution in Israeli and nationally-minded synagogues. It was therefore quite natural that those involved sought to continue the work and produce an additional siddur in the series for the non-Ashkenazi public.

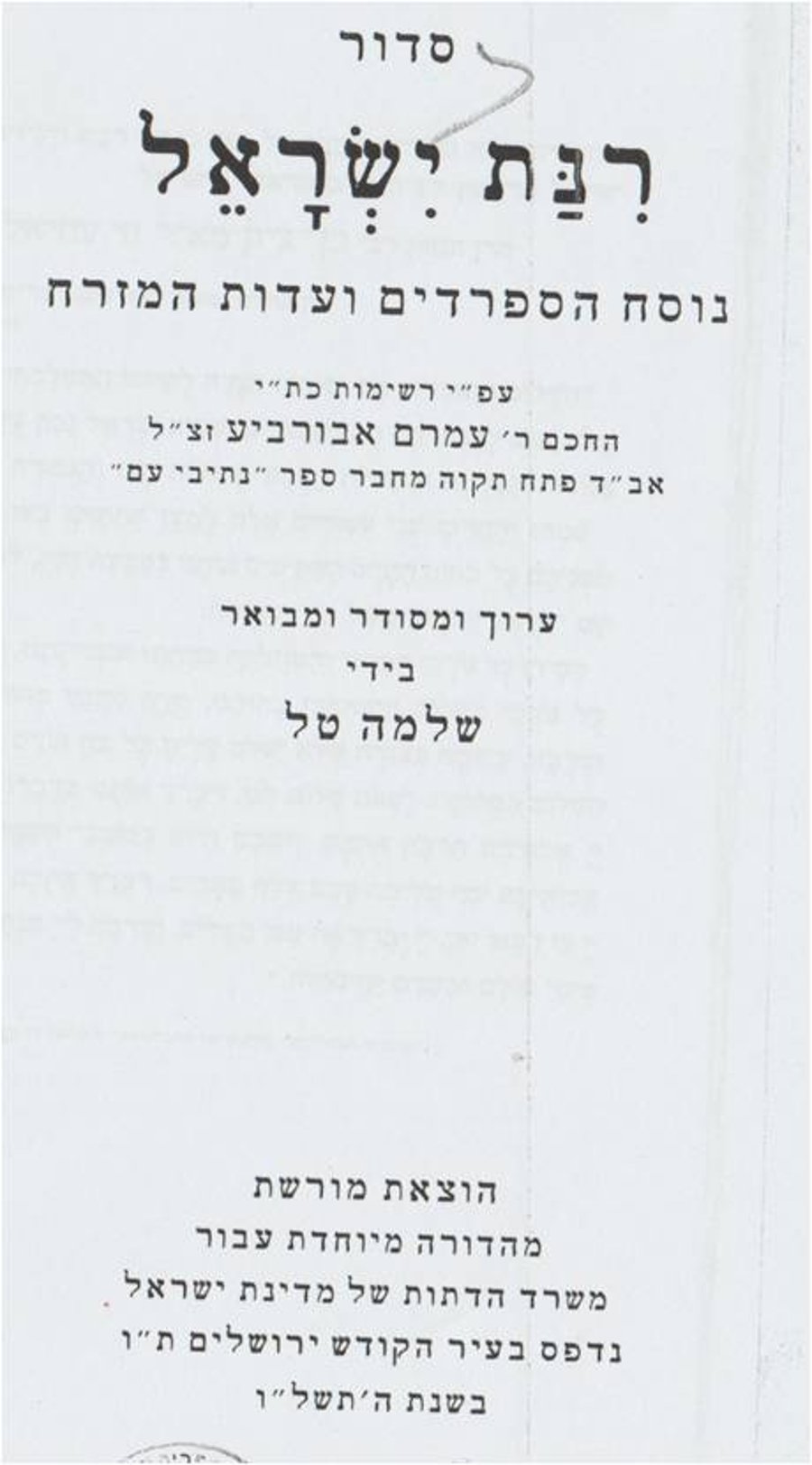

Thus, just as when the Ashkenazi siddurim were being produced a professional committee was quickly formed by the Education and Religion Ministries – as well as a committee of experts on Mizrahi prayer and nusach – and these tasked Shlomo Tal, the editor of the Ashkenazi siddurim in the series, with editing and producing the Mizrahi siddur.

True, there were people who protested giving the job of producing a Mizrahi siddur to an Ashkenazi editor. One of them, Moshe Rabi, even edited and annotated his own separate siddur, which he believed can better serve as the Mizrahi volume of the Rinat Yisrael trilogy. But in the end, the work continued, leaving the editors having to decide a number of core issues.

When it came to choosing the nusach of the siddur, for instance, there were a number Tal could choose from. He could select the well-known Babylonian or Iraqi nusach, based primarily on the rulings of Rabbi Yosef Chaim, better known as the Ben Ish Chai. He could go for the nusach of the Land of Israel and Aleppo, based on the rulings of Rabbi Yosef Karo, the Shulchan Aruch. Or Tal could choose a variety of North African nusachim of long standing.

However, due to his desire to ultimately lead to one uniform nusach for all, Tal ultimately chose to base his siddur on a kind of uniform Sefardi-Mizrahi nusach, formed at the time by Rabbi Amram Aburbeh, with the blessing of his mentor, Rabbi Ben Zion Meir Chai Uziel.

In order to fend off criticism of this choice, Tal included a special haskamah or statement of support from Rabbi Ovadyah Yosef, which included explicit reference to Rabbi Aburbeh and his work. The official name of the siddur was also meant to reflect this trend, declaring it was meant for both “Sefardim” and members of Mizrahi communities.

In terms of design and production, the third siddur in the series – published in 1976 – looked like its two Ashkenazi predecessors. But it did not enjoy their success in terms of popularity and public influence. It did make it onto the shelves of many schools and synagogues identified with the religious Zionist community in impressive numbers in the first few years. But then the trend reversed, and the siddur was ultimately marginalized in favor of other siddurim in Mizrahi synagogues.

The siddur’s limited success, at least in the long term, was due to a number of simultaneous factors. One was the creation of competing siddurs within a few years, some of which were cheaper, smaller, and easier to use. Another was the preference of many to adhere to the more precise nusach their fathers used instead of the quasi-uniform nusach which reflected no clear tradition. Most importantly, there was the halachic and political revolution of Rabbi Ovadyah Yosef, which led to the production of a number of Mizrahi siddurs based on his halachic approach and largely identified with his political approach.

Even if things appear to be changing once again, and a variety of Mizrahi siddurs and nusachs are slowly making their way to center stage, the Rinat Yisrael Sefardi-Mizrahi siddur will likely never meet the high expectations of its creators.

Nevertheless, it will remain a unique project, reflecting the precise time it was made: just before Rabbi Ovadyah’s revolution.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.