During the era of the British Mandate, synagogues throughout the Land of Israel underwent significant changes, driven by the desire of many of the congregants to demonstrate their support for the ideology and national ambitions of the Zionist movement.

This social-religious process influenced both the physical image and landscape of the synagogue and the form of the prayers said within. The architectural and internal design, the composition of congregants and the choice of those running the synagogue, the financial and organizational basis of the synagogue, and even the world of nusach, Hebrew pronunciation, and the siddur chosen for use in the synagogue were all chosen very carefully and deliberately.

This desire of many congregants and figures to adapt the siddur to fit the dominant ideological atmosphere in the country led to the creation of siddurim of a clearly national bent, distinguishing them from the older and more well-known traditional siddurim.

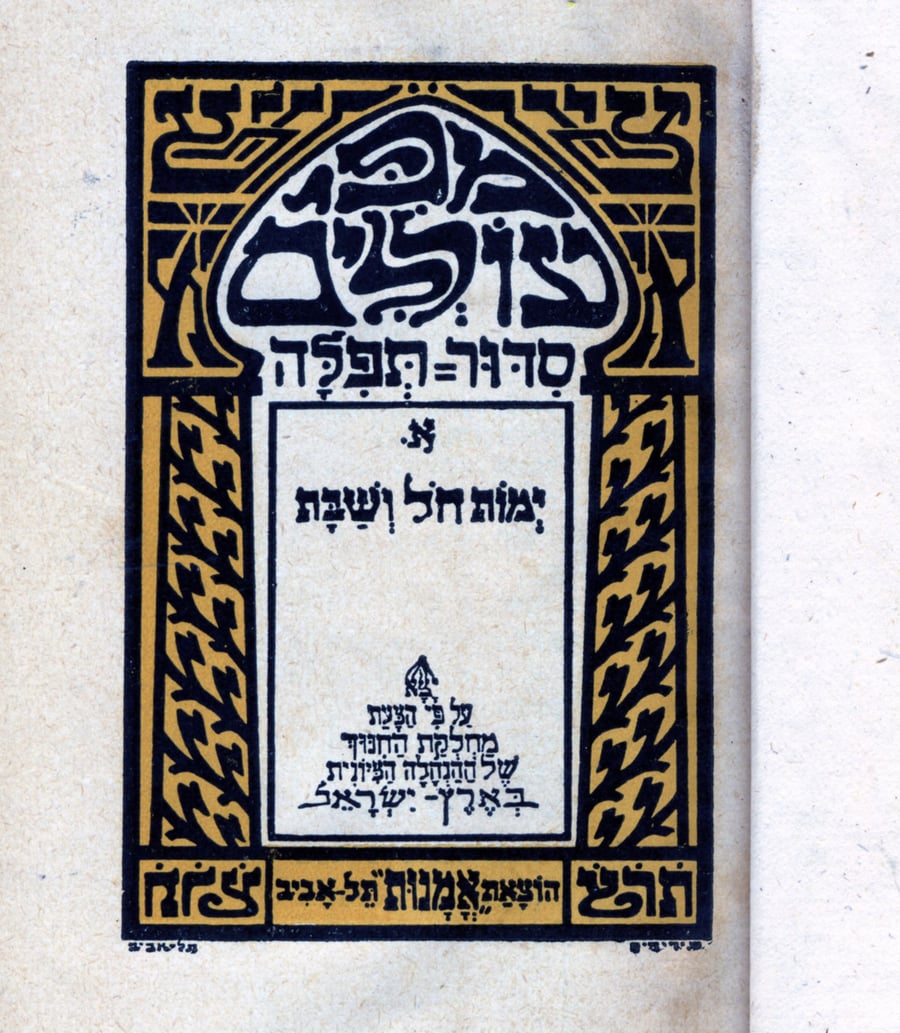

The story of the Mipi Olalim siddur [lit. From the Mouth of Babes], first published in Tel Aviv in 1930, is a clear example of just such an effort. As one can prominently see on the siddur’s cover, the initiative for producing the siddur came from Omanut publishing, a company headed by Shoshana Parsitz, member of the Zionist Executive’s Education Committee and of the Education Department of the National Committee, the official leadership of the Jewish Zionist community in the Land of Israel.

The publishing house was responsible for producing all the textbooks of the department for Zionist-run schools, and the Mipi Olalim siddur was thus considered inseparable from the educational and national project directed by Parsitz.

The actual work of putting out the siddur was assisted by a number of figures identified with the religious Zionist Mizrachi movement, including Rabbi Yaakov Berman (the movement’s representative in the Education Department), and the teacher and linguist Avraham Tzvi Zisserman (Naamani), who was charged with carefully editing the text of the siddur.

As a siddur meant primarily for students and teachers, editor Berman addressed a number of important educational issues in his introduction, including the need for gradual teaching of students depending on age, the connection between the siddur’s design and the different stages of prayer instruction, and so on.

The native and national character of the Mipi Olalim siddur was emphasized by its editors in a number of ways: the siddur’s cover openly declared itself part of the projects run supported by the Zionist executive in the Land of Israel. Easy and convenient Hebrew language instructions were placed in the siddur for school students. Most importantly, the prayer nusach was established in accordance with the “Eretz Israel” nusach established according to tradition by the students of the Gra, which was already seen by many – even if not entirely justifiably – as a symbol of the Land of Israel itself.

This choice of nusach was unquestionably an implicit statement of the siddur’s creators - a statement of commitment to the renewing culture of the Land of Israel, which would be based or try to be based on earlier native traditions and sources of the country.

In addition to the new page layout, Hebrew explanations, and choice of nusach, the visual design of the front inner cover of the siddur – created by artist Shlomo Yedidiah – clearly expressed the book’s Zionist and national foundations.

Yedidiah, a man of the Emek Ha’Arazim colony next to Jerusalem, worked for many years in developing ornaments based on the Hebrew alphabet and the landscapes of the Land of Israel. On the cover he designed for the siddur, he integrated well-known artistic forms from the Zionist art school of Betzalel, which felt innovative and surprising when adorning a traditional prayer book.

Aside from the siddur’s typography and page layout, even the paper used by the creators of the siddur was particularly thick and well-made, especially compared to the poor quality of siddurim put out by publishers of the traditional siddurim, and the cover was also made of high-quality material.

At first, just two editions of Mipi Olalim were published, for weekdays and for Shabbat, one in the Ashkenazi or “Eretz Israel” nusach and one in nusach Sfard, and these were now at the heart of prayer education in Zionist schools. A few years later, the series also included machzorim for Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot and for the High Holidays – though this began as a private commercial effort rather than a national project.

Either way, unlike the long-standing success of the machzorim, which were printed in many editions, the first siddur in the series and the most clearly ideological one, which included prayers for weekdays, practically disappeared from view and was not widely distributed – in schools or among the public at large.

Those who still possess it at home would do well to flip through it from time to time, so they cam remember the spirit of an age and the ambitions which drove the production of this unique siddur.