What will happen to ancient Jewish shuls after Syria's civil war?

Jewish heritage sites face uncertain future in Mohammed Al-Julani's Syria

Ancient Jewish synagogues and religious artifacts are at risk during the current political upheaval in Syria.

As Syria enters a new chapter following Bashar al-Assad's fall from power, experts are raising alarms about the fate of the country's Jewish historical sites, many of which have already suffered extensive damage during the 13-year civil war.

The conflict, which claimed over 600,000 lives and saw 100,000 people disappeared into prisons, has taken a heavy toll on Syria's cultural heritage – including remnants of its once-thriving Jewish communities that date back more than two millennia.

"Many of these sites have had no caretakers for decades," explains Dr. Emma Cunliffe, an archaeologist at Newcastle University's Cultural Property Protection and Peace team. "During the conflict, existing neglect intensified dramatically, and access became nearly impossible for the few remaining caretakers."

The scale of destruction is staggering. By 2020, nearly half of Syria's Jewish heritage sites had been destroyed, according to the Foundation for Jewish Heritage. Notable casualties include the historic Jobar Synagogue in Damascus, which was reduced to rubble in 2014, with its precious Torah scrolls, tapestries, and artifacts disappearing – some later surfacing in Turkey.

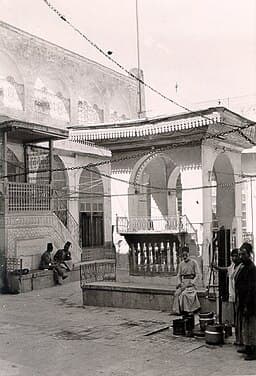

The al-Bandara Synagogue in Aleppo, one of the city's oldest, sustained significant damage during heavy fighting in 2016. In Tadef, a town east of Aleppo, a shrine to the Jewish prophet Ezra fell victim to illegal excavation and looting by both rebel groups and government forces between 2021 and 2022.

Particularly concerning are the Roman-era synagogue ruins in ancient cities like Dura-Europos. Satellite imagery revealed extensive looting while the site was under Islamic State control. While some artifacts, like the 40 ceiling tiles preserved at Yale University Art Gallery, are safe, experts fear many others have been stolen.

The situation reflects the dramatic decline of Syria's Jewish population over the past century. From approximately 100,000 Jews in 1900, numbers fell to 15,000 by 1947. Following anti-Jewish violence and Israel's establishment in 1948, the community dwindled further. By the time Assad's regime allowed Jewish emigration in 1992, only about 4,000 remained. Today, that number has dropped to just three.

As Syria transitions to new leadership with roots in Islamic fundamentalist movements, the future of these historical sites remains uncertain. While the new regime has shown signs of pragmatism in recent years, questions linger about its approach to minority cultural heritage.

"The preservation of these sites depends heavily on local support and an inclusive society," says Cunliffe. "With ongoing conflicts and an unclear political future, the ultimate fate of Syria's Jewish heritage will largely be determined by whoever emerges victorious."

Assessment of the full damage remains challenging, hampered by limited forensic capabilities in the war-torn nation and the Syrian Antiquities Authority's minimal budget. Satellite imagery analysis is expected to take months, while establishing meaningful protection for these sites could take considerably longer.

Arutz Sheva contributed to this article.