A Siddur A Week

A Siddur A Week: The Tefillat Kol Peh Siddur and Its Influence

How large letters and an insistence on fullness rather than minimalism made the Tefillat Kol Peh siddur one of the most enduring prayer books in Israel.

Rabbi Yaakov Shaul Halevi Weinfeld made Aliyah to the Land of Israel in 1935. Before setting out, he loaded printing equipment onto the ship. The print shop now being moved to another country belonged to his father, David Yoel Weinfeld, who hailed from the Polish city of Sanok. It included a machine for casting lead letters, as well as old printing matrices of unknown origins. A few decades later, the books it had served to print in Poland served as the basis for what would become the most widespread siddur in the Land of Israel, influencing dozens of its successors.

Weinfeld settled near Meah Shearim neighborhood in Jerusalem, where he reestablished the family print shop, which would come to be known as the Eshkol publishing house. Over the years, his form focused primarily on producing basic sifrei kodesh, while explicitly taking care to print in large, clear letters and maintain a high standard of grammar and proofreading.

Among its products was new editions of the Sefer Hachinuch, a complete set of Mishnayot, Nevi’im and Ketuvim with commentaries, and Machzorei Rabba, which were popular in their own right. But there is no doubt that Weinfeld’s most successful undertaking, at least in terms of raw numbers, was the Tefillat Kol Peh siddur, which quickly took large swathes of the country’s market by storm, remaining fairly common until today, over half a century after its appearance.

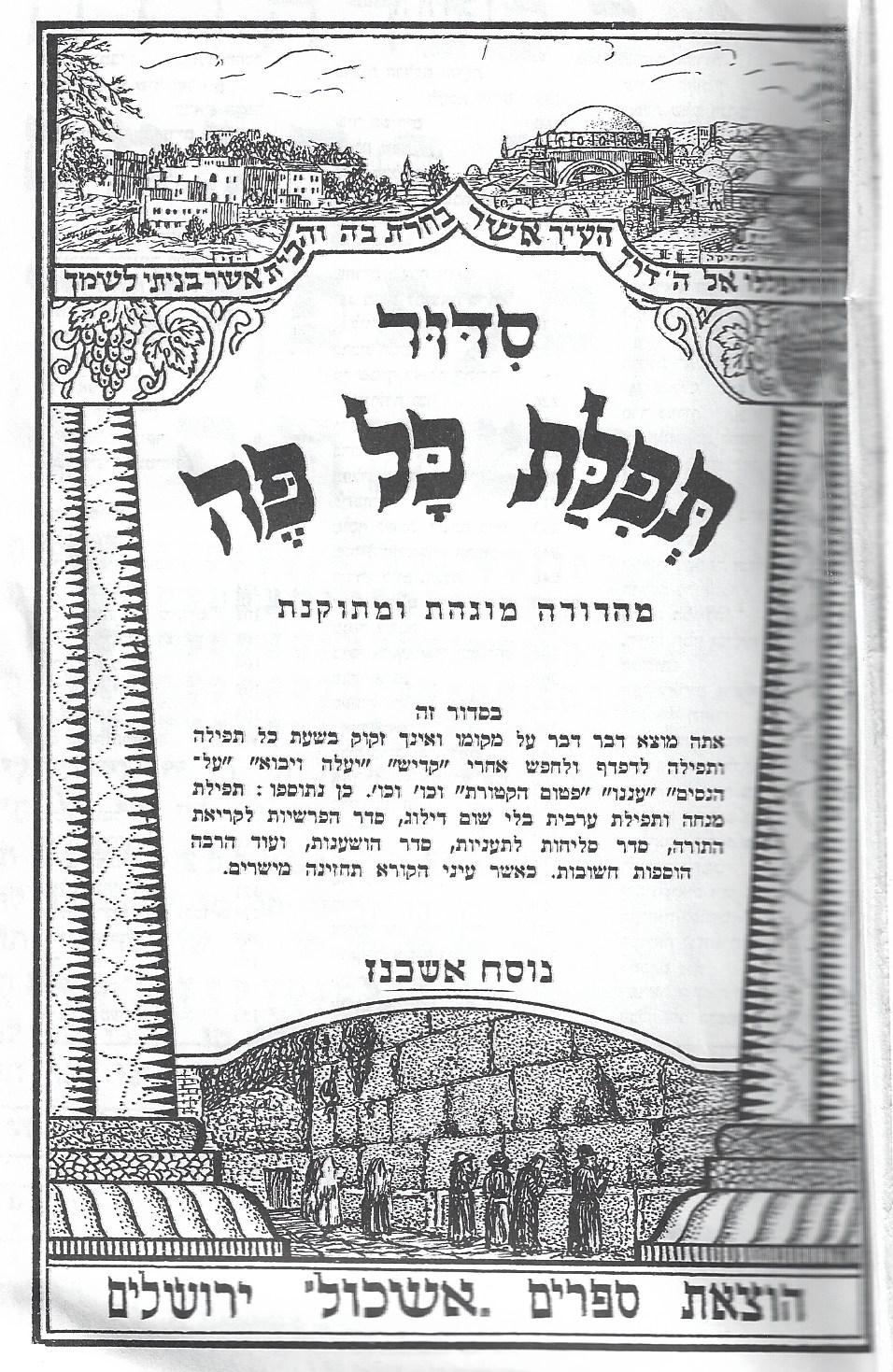

The siddur’s first edition, which came out for both Nusach Sfrad and Ashkenaz – appears to have first been published in 1964. The inner cover announces its purpose and uniqueness:

“In this siddur, you find everything in its place, and you need not flip through the pages and look for kaddish, yaaleh veyavo during any prayer […] also added: Minchah and Arvit prayers without any skipping, the order of parshiyot for reading Torah […] and many more important additions.”

There is no doubt that compared to siddurs like Or Mitziyon – whose editors skimped on both paper and space – the Tefillat Kol Peh siddur was a real upgrade. The slew of new editions that came out – some of which were called “The New” Tefillat Kol Peh – contained more and more elements, such as the shir shel yom chapters according to the Gaon of Vilna, printed on the inner cover of the siddur – including, amazingly enough, the Nusach Sfard version.

Weinfeld’s descendants say that the name of the siddur – which combined elements originally published outside of Israel and ones which were redesigned – derives from the saying “for you hear the prayer of every mouth [tefillat kol peh],” which is the version of the “Shema Koleinu” blessing in the Nusach of Chasidut. It should be noted that this name was also used for many previous siddurim, both in Europe and in the Land of Israel, and used for many different nusachs: Yemenite, Mizrahi, and Ashkenazi.

The siddur’s innovations could even be seen in the inner cover, which was probably designed by artist Moshe Cohen. True, like the more nostalgic cover of the Or Miztiyon siddur, the Tefillat Kol Peh’s cover placed Jerusalem at the center.

But Tefillat Kol Peh’s Jerusalem combined old and new: alongside the traditional image of the Western Wall and a new drawing of the Old City and the Hurva synagogue – which appeared in the upper right part of the page – the homes of the new Jerusalem outside the walls were also included, as if to say that the siddur had its feet firmly planted in both past traditions and current realities. This duality between old and new could also be seen in the brief prayer instructions integrated into the siddur: some of them were written in “Rashi script,” bearing the mark of traditional Jewish religious printing, but also a gradual move to more modern block style.

Within a few years, the siddur attracted the attention of many communities – both Charedi and non-Charedi. True, many could point to multiple nusach and proofreading issues, as well as the inconsistency in design and editing choices, and many religious Zionists felt unease at the absence of the national prayers.

On the other hand, there is no doubt that the new pagination and large fonts attracted many a teacher, gabbai, and congregant, making it one of the most widely used siddurim. To this day, many identify the siddur with various prominent elements, such as the alphabetical reading and pronunciation table in the beginning of the siddur – making it a great learning tool for school children – and a single section for weekday Minchah and Arvit prayers, with them both appearing on the same page, separated by an underline.

The many editions of the siddur which appeared since its first production, including specially thin ones for school students, influenced not only those who prayed from the siddur itself, but also quite a few of the siddurim which came after, both in terms of content.

In any event, many tie Ashkenazi prayer in all its nusachs to the graphical and content choices made by Weinfeld, which endure decades after his death.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.