When it comes to the world of Jewish prayer, Rabbi Shlomo Goren, the country’s first Chief Rabbi for the IDF, is mostly remembered for his effort to establish a “uniform prayer nusach” for both soldiers and the broader public. But this uniform nusach, which he began to distribute in the early 1960s - and which was largely based on the Ashkenazic/Chassidic “Sfard” nusach – was not his first try at shaping prayer in the nascent Jewish state, especially among the soldiers, whose spiritual and Jewish world were his to develop.

Thus, the army produced a number of siddurim for IDF soldiers already in the early 1950s, which included new liturgical elements – some of them unfamiliar – and which prominently expressed Rabbi Goren’s feelings about the historic moment in which he lived.

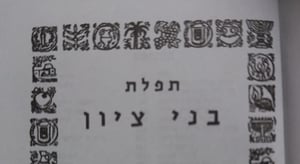

One of those siddurim, produced with the title “A Siddur For the Soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces,” was published in a small format and in Ashkenazi nusach already in 1952, four years after the state itself was founded, and it included a number of interesting and unique elements. Interestingly enough, this siddur was printed at the Levin-Epstein Brothers print shop in Jerusalem, which despite the long-standing sympathy of some of its owners for the Zionist idea, is not popularly remembered as a source of nationally-minded siddurim and books.

The siddur’s inner cover contained the symbols of all the corps of the army (including a number of corps which no longer exist), with the bottom of the page noting that the siddur appeared in “the fifth year of the State of Israel.” The siddur begins with a “prayer before battle for the soldiers of the IDF,” which Rabbi Goren wrote himself, and which is preceded by Rabbi Goren’s call to all the soldiers, including his hope and belief that “The army of Israel, from the beginning of its path, in being sanctified to war, in marching towards the battle, cast its eyes in prayer to Heaven, and its heard longs for God who gives it strength, protects it, and serves as its bastion in time of trouble.”

As a siddur meant for soldiers, wherever they are, the book includes the prayers for every day of the year – including the High Holidays. The siddur’s simple and non-uniform design attests to its production and design being based on previous siddurim put out by Levin-Epstein, probably due to financial considerations, with new additions added in later.

Due to this modus operandi, the new elements were introduced in the first part of the siddur, as well as the four non-numbered pages in the middle of Shabbat prayers, between “Mi Sheberach” for the community and the prayer for the new month. It should be noted that these pages did not contain the prayer for the State of Israel, probably because neither the prayer itself nor the appropriate time to say it during prayer had become widely accepted and established among the broader public at the time.

Although the prayer for the state was absent, these extra pages in the heart of the siddur contain a complete prayer in memory of IDF soldiers (in both traditional “E-l Malei Rachamim [God, Full of Mercy]” and new “Yizkor” form), as well as the prayer for the soldiers of the IDF. Rabbi Goren also wrote this prayer, an early version of which contained a brief prayer for the state and its leaders: “He who blessed our forefathers, Avraham, Yitzhak, and Yaakov, he should bless the President of the State of Israel, the Prime Minister of Israel and its ministers, the Chief of Staff and his fellow commanders, and all the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces.”

Aside from these, the only other added feature in the siddur is the complete order for counting the Omer, which was attached to the back of the siddur and whose pages were properly numbered.

The siddur’s small form was probably convenient for most soldiers, and its traditional internal design probably reflected what they were often familiar with from the synagogues of their youth – especially those who hailed from Europe, including survivors of the Holocaust. On the other hand, the outer cover and the nationally-minded additions undoubtedly expressed feelings of a momentous historic era, which Rabbi Goren was far from alone in feeling.

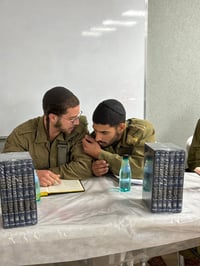

In these days of war and conflict against a dangerous enemy, and with Israeli society still reeling from the wounds of its previous internal conflicts, I flip through the siddur and seek to feel something of that wonder and hope, taking care to pray with it, for us.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.

0 Comments