Every synagogue is beloved by God, and every synagogue is dear to its congregants. But there are a number of synagogues – spread throughout the Jewish diaspora, past and present – which have acquired a particularly meaningful communal and religious status, serving as a sort of lighthouse for preserving tradition, nusach, and custom, which most of their community is committed to and whose memory they cherish.

So it is with the El-Ghriba synagogue in Djerba, the Tsalat al-Kabri synagogue in Baghdad, the ancient synagogue of Aleppo. The Kanis Bayt al-Usta in Sanaa, Yemen ranks among these illustrious institutions. The unique status of this synagogue has been expressed over the years in the attempts of many Jews to preserve its precise customs, 70 years after it ceased to function.

The Kanis Bayt al-Usta was founded in Sanaa centuries ago, and was known already in the 18th century as one of the local community’s most prominent spiritual centers, with leaders taking care to pray and learn there. In 1762, the synagogue was destroyed along with many others by the order of the Yemenite authorities. It was later rebuilt and returned to its position as one of the most important synagogues in Yemen.

In one description of the synagogue from the early twentieth century, we learn of how “the light of Torah always shines within, evening and morning. And all its people are men of valor, God-fearing, hateful of profiteering, honest of heart” (Rabbi Machputz Jerufi, Magid Tzedek). The prayer nusach used in the synagogue was the “Shami” one (based primarily on the Sefardic prayer nusach, and containing many kaballistic elements), but it also included customs unique to all Sanaa synagogues – with their own prayer formulas.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, the yeshivah and synagogue was headed by Rabbi Sa’id Ozeri (1869-1954), who merited making Aliyah to Jerusalem, where he settled in the Katamonim neighborhood. His star student, Rabbi Yosef Tzuberi (1916-2000), had made Aliyah already in the forties, quickly becoming one of the most prominent Yemenite Rabbis in the country and the Rabbinic leader of the Yemenite community in broader Tel Aviv.

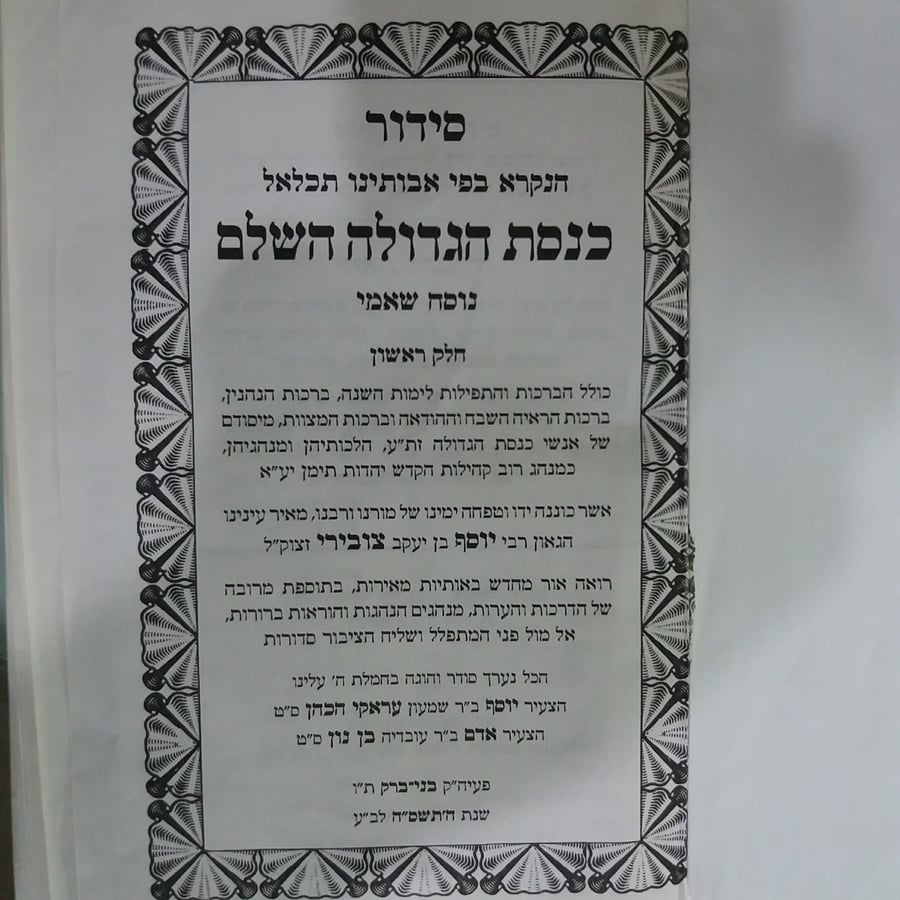

In 1976, he published the first edition of his Knesset Hagedolah siddur – which would later be expanded to four volumes, including all prayers year-round – and for which he even received a prize for Torah-halachic works. Given the mixture of customs and traditions which formed once the Yemenite Jewish community made Aliyah to Israel – and the education of the younger generation in non-Yemenite Torah institutions – Rabbi Tzuberi took care when editing the siddur to first and foremost preserve not only the Yemenite-Shami nusach as a whole, but also the customs of Sanaa, especially the perpetuation and preservation of the customs of the synagogue he'd grown up and learned in – the Kanis Bayt al-Usta.

And indeed, his siddur became widespread, with synagogues throughout the country – both in the Katamonim neighborhood and elsewhere – declaring that since its release, they have followed the custom of Sanaa’s illustrious synagogue, whose greatness was told of by their parents.

Rabbi Tzuberi passed away in 2000. Five years later, a new edition of the Knesset Hagedolah siddur was published, Edited by Yosef Araki Hacohen and Adam Bin Nun. This edition – as the editors note in the preface – includes corrections and completions also on the basis of Rabbi Tzuberi’s notes, which he wrote for himself but did not manage to integrate into the new edition of his siddur:

“And we found in the archive of our teacher and Rabbi ob”m, many of these pages, and we rejoiced in them as though we’d found a great treasure […] and it was already known and publicized how many were his troubles […] his one hand held a pen and his other hand served the people. And many times he would stop in the middle of writing a word to respond to a questioner entering his home.”

And indeed, a reading of this edition shows it to contain multiple layers of Yemenite custom: Shami, Sanaani, and in various places also customs native to the modern-day Land of Israel. The siddur also contains exacting descriptions of less accepted customs, such as saying the thirteen middot of God while sitting down, or saying the viduy confession without beating one’s chest in the heart area.

How many more generations will it be possible to continue and preserve such customs of synagogues no longer used or nearby? It’s hard to tell. But there is no doubt that the very effort demonstrates the congregants’ appreciation of the synagogue, as well as that of our generation for the previous ones.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.

0 Comments