Back when I was coming of age politically, Yisrael Kessar was the public face of the Histadrut, Israel’s largest general workers’ union. He declared labor disputes, he spoke at protests in front of the government, and he was the one to announce – together with the Finance Minister – that a “package deal” had been signed.

At one of those protests, so the story goes, a surprised journalist found him secluding himself from the rest of the protestors and reading a small book. Kessar responded to the journalist’s astonishment by saying that the protest can certainly continue without him. If, however, he arrived at Shabbat shacharit morning prayers without first preparing the Torah reading, it would be particularly embarrassing for him. Kessar’s unique – and personally and publicly controversial – character led to the creation of a Yemenite siddur which has since been forgotten – Tefilat Shivtei Yisrael.

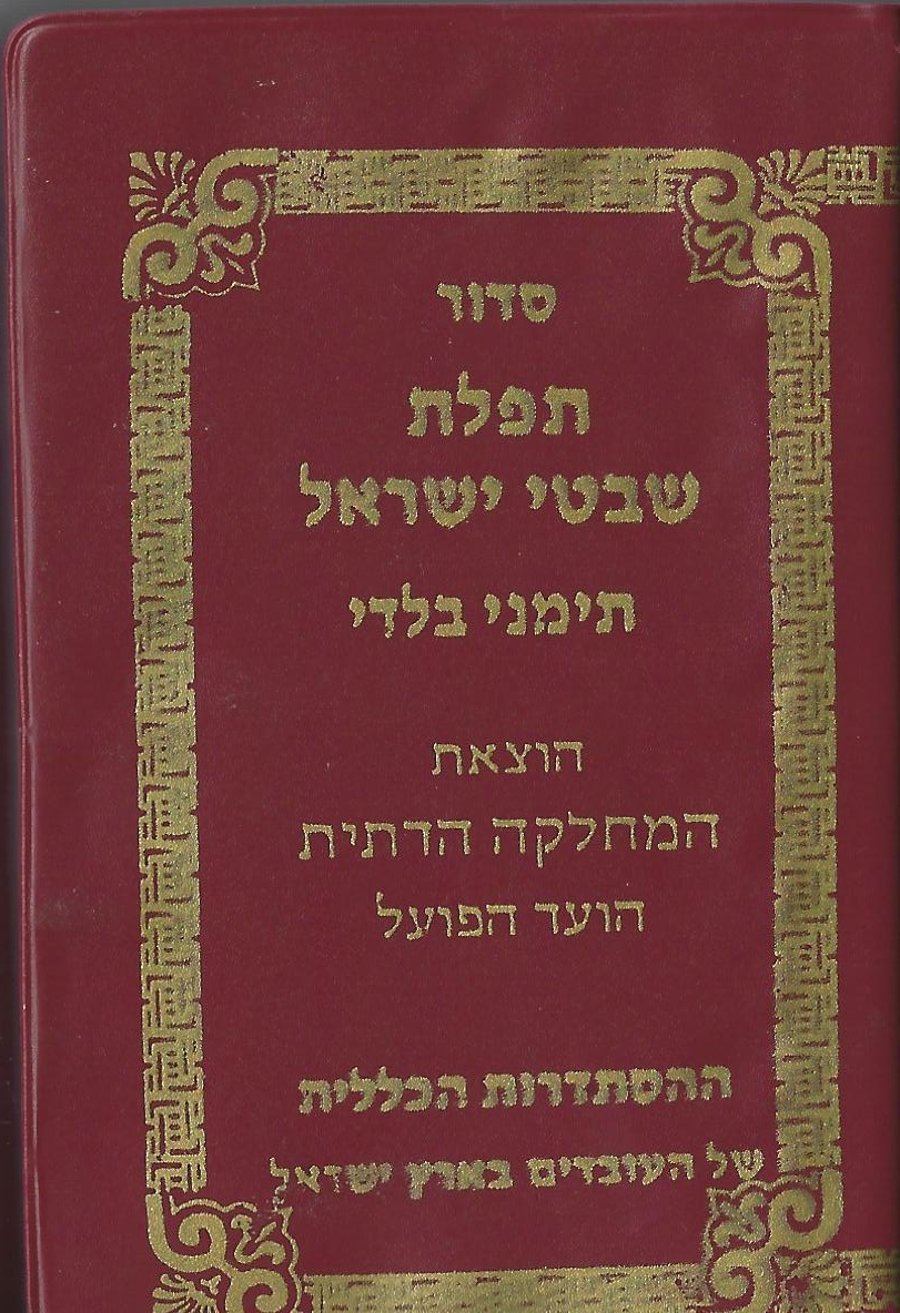

The production of the siddur – whose unique dimensions (6.5 X 10.5 cm) made it the smallest Yemenite siddur made to this day – took place in the early 1990s, probably a short time before the elections of 1992. The Histadrut’s religious department had enough money to realize a unique project: to provide religious members of the Histadrut with their own siddur, which would explicitly connect religious and socialist values. In addition to Kessar himself, the effort was led by Rabbi Zechariah Hami, Chairman of the Histadrut’s religious department, who served for many years at the head of Ramat Gan’s religious council and as one of the leaders of the Yemenite Jewish community in Israel. And indeed, the new siddur was arranged and designed in a fairly short time, appearing in two nusachs: Sefard and Yemenite-Baladi.

Due to the siddur’s tiny size, the prayer text was redesigned specially for the Histadrut (based on the bolded Vilna font, interestingly enough), ultimately numbering 466 pages. Added to this were the congratulations of Yisrael Kessar himself, printed on the inner part of the front cover, and that of Rabbi Zechariah Hami, his partner in crime, which was put on the back cover. The soft and simple siddur’s red cover turns out to have been deliberately chosen, as was the decision to prominently declare on its cover that the siddur was produced by the “Religious Department Publishing, Executive Committee, General Histadrut of Workers In The Land Of Israel.”

Like some other siddurim, the Yemenite siddur begins with the prayer for saying Shema before going to sleep. But already on the first page, the siddur explicitly says that “this is the order of blessings and prayers per our custom in the (holy community) of Sanaa and all the cities of Yemen (may God protect them).” Sanaa was not mentioned by accident: it was the source of the precise nussach handed down in its synagogues and yeshivahs for generations, as well as the birthplace of Yisrael Kessar himself, who left it to make Aliyah to the Land of Israel in 1933, at the age of two.

However, there are a number of places in the siddur containing religious customs created in the wake of the Zionist movement. As the siddur of an Israeli union, it should be no surprise that it contains the customary prayer for the ruler, adapted to modern times (“to the government of Israel, may its glory ascend”) and also a prayer for the soldiers of the IDF (“our armies and defenders, heroes of Israel, who serve and volunteer among the nation to fight the holy war”).

A few months after the siddur came out, the Labor Party won the election. Yisrael Kessar was appointed Transportation Minister and had to step down as Secretary-General of the Histadrut. The siddur he produced with Rabbi Hami was also quickly forgotten, and is not even included in bibliographies of Yemenite siddurs produced in Israel. However, there are probably still hundreds of homes throughout the country where you can find an old copy, a testament to the people who ensured its creation, as well as the image of the Histadrut itself, a mere generation ago.

My thanks to Yaakov Karavani for his help in supplying information.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.