In a small publishing house he managed next to the Machaneh Yehudah market, on 1 Meyhuas Street in Jerusalem, Salah Mansour created the siddur which would become the most widely used prayer book among Mizrahi Jews in the Land of Israel. Indeed, many considered his Tefilat Yesharim siddur to be an almost official nusach, by which other siddurim would now be measured and under whose large shadow they now existed. However, it would seem that only a small portion of those who prayed with it could truly understand the deep spiritual outlook which led to the siddur’s creation and the design of its content.

Yaakov Mansour, the publisher’s father, lived in Baghdad, and was a regular guest of the senior Iraqi Rabbis of the time, including Rabbi Yosef Haim – better known as the “Ben Ish Chai.” Salah Mansour learned the Iraqi prayer customs from his father and his Rabbis as well, as well as the effort they devoted to maintaining daily kabbalistic customs and traditions.

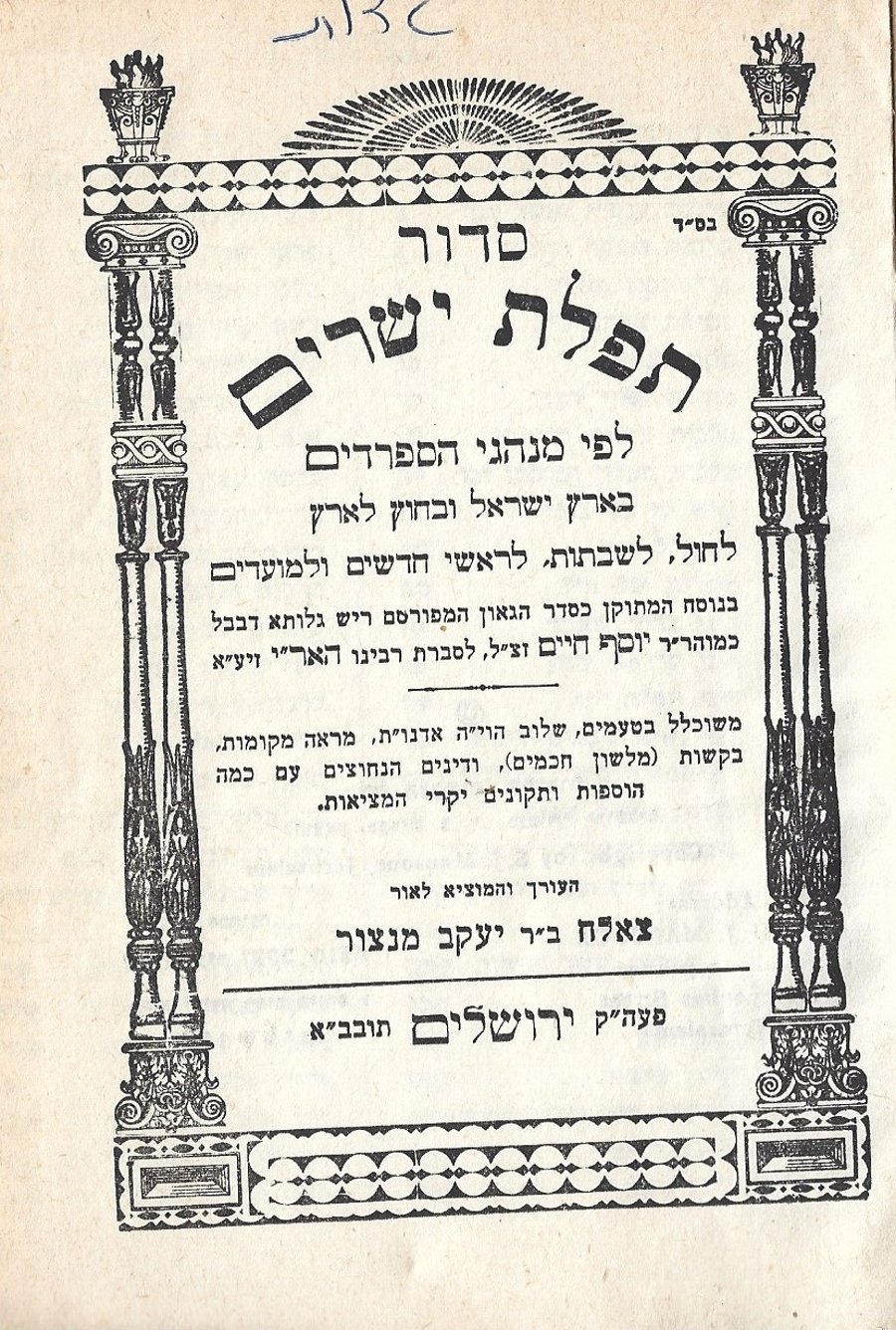

When he made Aliyah in the nineteen twenties, he sought to preserve the Baghdadi nusach, as well as all those customs drawn from the world of kaballah which his teachers so assiduously followed. And indeed, on the inner cover of the siddur – whose first edition was published around 1938 – Mansour explicitly declared that it was arranged “in the proper nusach as the order of the Gaon Hamefursam, Reish Galuta De-Bavel Ke-Morenu Rav Rabbi Yosef Haim zatzal, per the opinion of Rabeinu Ha’Ari,” and that it, naturally, includes, “the honing of te’amim, the inclusion of [Shem Havyah in Adnut], a mar’e mekomot, bakashot (in the language of the Sages), and needed denim.”

Mansour’s commitment to the Iraqi custom was also marked by a number of places in the siddur explicitly saying that “here we start in Baghdad.” Some of the early editions even contained a number of translations into Iraqi Judeo-Arabic.

The great success of the siddur – which was apparently the most widespread among Sefardi and Mizrahi Jews until the eighties – can be attributed to a number of factors: the complete and precise nusach, the generous inclusion of instructions and customs, the halachic standing of the Ben Ish Chai, the leading role of the Iraqi community in shaping the Mizrahi-Israel worldview, the siddur’s small and easy to use format, and probably also the very mention of Jerusalem, which was prominently displayed on the cover. Few probably knew of the simplicity and modesty of the publisher and of the small size of Mansour’s store – whose current incarnation is still in operation on Sfat Emet Street, very close to its original abode.

Like other publishing houses, Mansour also produced a range of editions for his siddur, which were meant for weekdays, Shabbat, and various holidays. One of the most common of these was the one which included just Minchah and Maariv, alongside chapters of Tehillim, verses from the Tanach, bakashot, and more. In 1946, he even sought to publish a thinner and cheaper educational version of the siddur, omitting the tikkun chatzot, the seder of the four fast days, and a significant portion of the traditional instructions and traditions included in the complete version.

With the founding of the State of Israel, new siddurim began to appear, some of them based on the nusach of the various Mizrahi communities. Still, for the first few decades, Tefilat Yesharim maintained its dominant status and remained the most widespread and accepted siddur, especially in Jerusalem but also throughout the entire country (and sometimes even beyond). Like other siddurim, the national prayers such as the one for the State of Israel began to creep in gradually and hesitatingly, while appearing – at least in some cases – at the end of the siddur, as though their halachic and religious status still requires clarification and acceptance.

But in the end, even Tefilat Yesharim’s unique standing couldn’t withstand the spiritual, ideological, and historical forces which ultimately pushed it to the margins of the Mizrahi shul. Thus, with the rise of the halachic method of Rabbi Ovadyah Yosef, which its reliance on the Shulchan Aruch (and contra the Ben Ish Chai) and including fewer kabbalic practices in prayer, new siddurim began to appear from the eighties onward, and the shuls which accepted them practically did so as a declaration of loyalty, both to Rav Ovadyah himself and to his social and political project.

Thus did Mansour’s siddur find itself being pushed off the stage, and few are the shuls today which still offer it to congregants, as hundreds did for close to half a century.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.

0 Comments