Praying in Father’s Font: The Rise and Disappearance of the Or Mitziyon Siddur

For more than a half a century, the Or Mitziyon siddur, with its visibly grim and old-fashioned appearance, was one of the most widespread siddurim in the Land of Israel. It appears to have only been printed in the country starting in the early thirties, but this was done with printing matrices brought from Poland, which were quite overused and worn out by then.

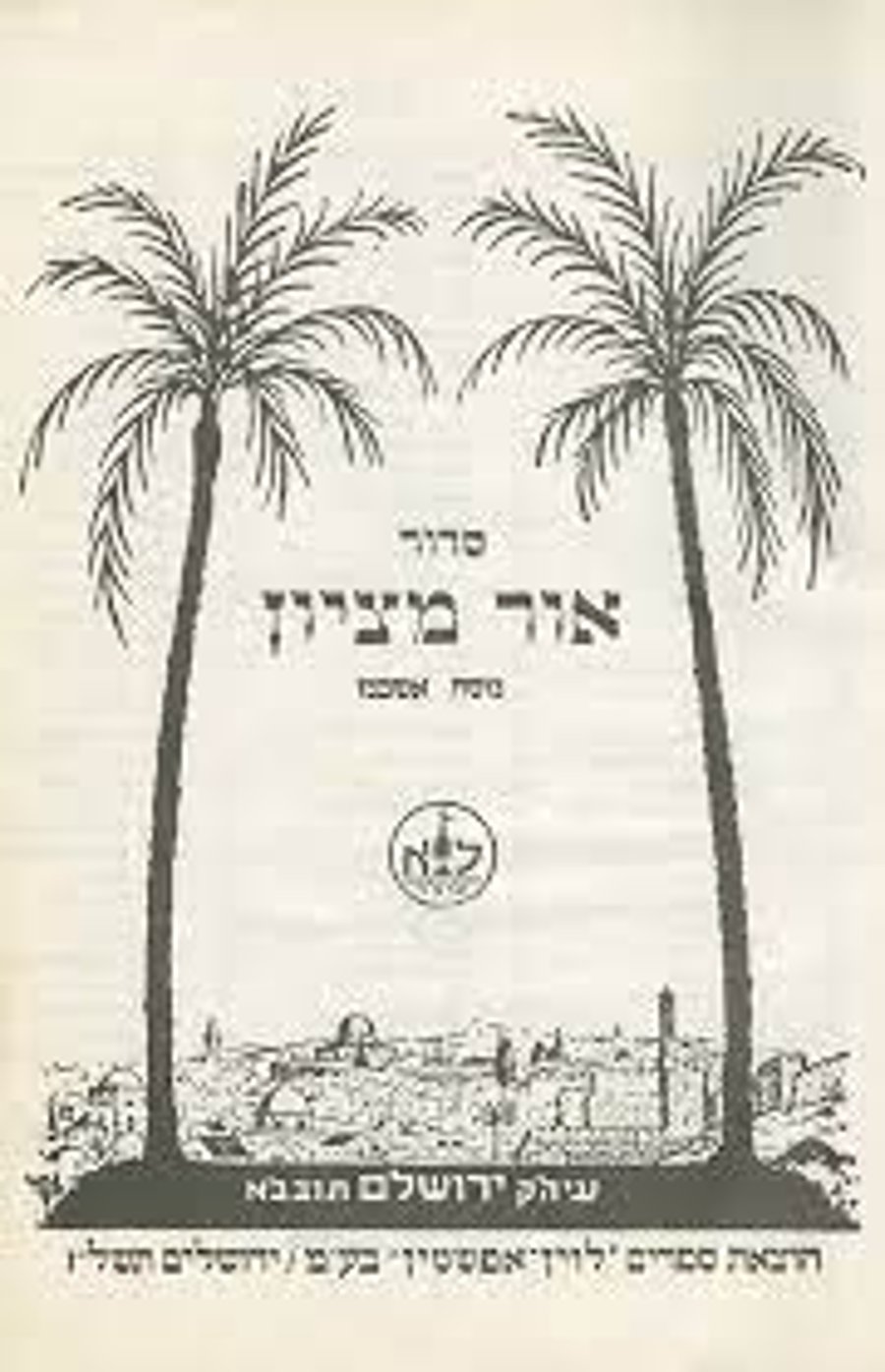

From here on out, dozens more editions of the siddur were printed for a number of nusachim and sometimes accompanied by a variety of additions - most of them marginal. Still, its basic features remained in place until the end: sparing use of pages and spaces, a range of letter sizes, whose logic is not always clear, a particularly challenging internal system of references, and above all – an inside cover with a classical illustration of ancient Jerusalem, flanked by two palm branches.

We have no way of knowing who put together the first few editions of the siddur and who made the decisions regarding nusach, design, and production. When it comes to the publishers who put out the siddur in the Land of Israel – Levin Epstein and its changing partners – we actually know quite a bit.

The publishing house started life in Wilkowischki in Lithuania in 1865, where it was founded by Shmuel Levin-Epstein, one of the descendants of the Maharsha. A few years later, they moved to Warsaw, only to move again to the Land of Israel at the beginning of the British Mandate. After making “Aliyah,” the publishers focused primarily on putting out what were known as “romel” books (simple “fair books,” usually chumashim, siddurim, and the like), the most prominent of which, at least in terms of quantities and sales, was the Or Mitziyon siddur.

Like the original creator of the siddur, the name of the artist who created the siddur’s famous inside cover remains anonymous. True, the artistic conventions on which the cover’s illustration is based are reminiscent of those used by very well-known artists, including Ephraim Moses Lilien and Zeev Raban (who appears to have also illustrated the cover for a collection of kinnot put out by Levin Epstein). Still, the artist’s full name is not mentioned, and the general appearance of the cover – preserving the image of late 19th century Jerusalem – perfectly fit the conservative character of the siddur as a whole.

As we said, the siddur also had a number of different and unique editions. Alongside the classic siddur, otherwise known as Or Mitziyon Hashalem, two editions of the siddur were published in the thirties which were defined as being meant for children – “for tinokot of Beit Rabban.” One was in nusach Ashkenaz – accompanied by instructions and guidance in Hebrew, and the other was in the nusach of the Ari (Sfard), which was accompanied with halachic instructions in Yiddish, at least at first.

These editions only deviated slightly from the original, primarily emphasized by the large fonts used for the central prayer sections, making things easier for students starting out on their prayer journey. Other unique editions were published in the fifties and sixties, in which a number of pages containing the national prayers devoted to the State of Israel and its Independence Day were clearly and artificially attached to the end of the book. This was no doubt done to try and attract new audiences, but was also in accordance with the character of the publishers as a whole, who were generally conservative but occasionally identified with the Zionist project.

From the sixties onward, the siddur faced more and more competition, in addition to old rivals like the Shirah Chadashah siddur. The greatest challenge ultimately came from the nationally-minded Rinat Yisrael, which began appearing in a variety of nusachim from 1970 onward, and which offered congregants an alternative in terms of design, ideology, and even Torah learning. Despite this, many continued to use Or Mitziyon – even distributing it in clearly religious Zionist schools. This was probably thanks to its cheap price, its light weight (and thin paper) and most importantly due to its being recognizable, accepted, and even beloved siddur, a conservative institution.

The final editions of Or Mitziyon were likely prepared in the mid-seventies, but even afterwards, the siddur continued to be quite widespread – especially in Charedi or more conservative communities, or in old style Jerusalem shuls.

Today, by contrast, it can only be found in a few shuls and with great effort, pushed to the corner of the shelf or hidden behind the row of new, far more elaborate siddurim. Despite this, I find myself rejoicing anew every time I get the chance to flip through and pray one more time with a siddur which did so much for the world of prayer, kavanah, and berachah.

Dr. Reuven Gafni is a senior lecturer at the Land of Israel Department at Kinneret College. He specializes in the field of synagogues and religion in the Land of Israel in the modern era, and the relationship between Jewish religion, culture, and national identity in the Land of Israel.

0 Comments